Charles Mauldin was near the front of a line of voting rights marchers, walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965. He was 17 at the time, joining others in protest against the refusal of white officials to let Black Alabamians register to vote, and the recent killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a minister and voting rights organizer, who had been shot by a state trooper just days earlier.

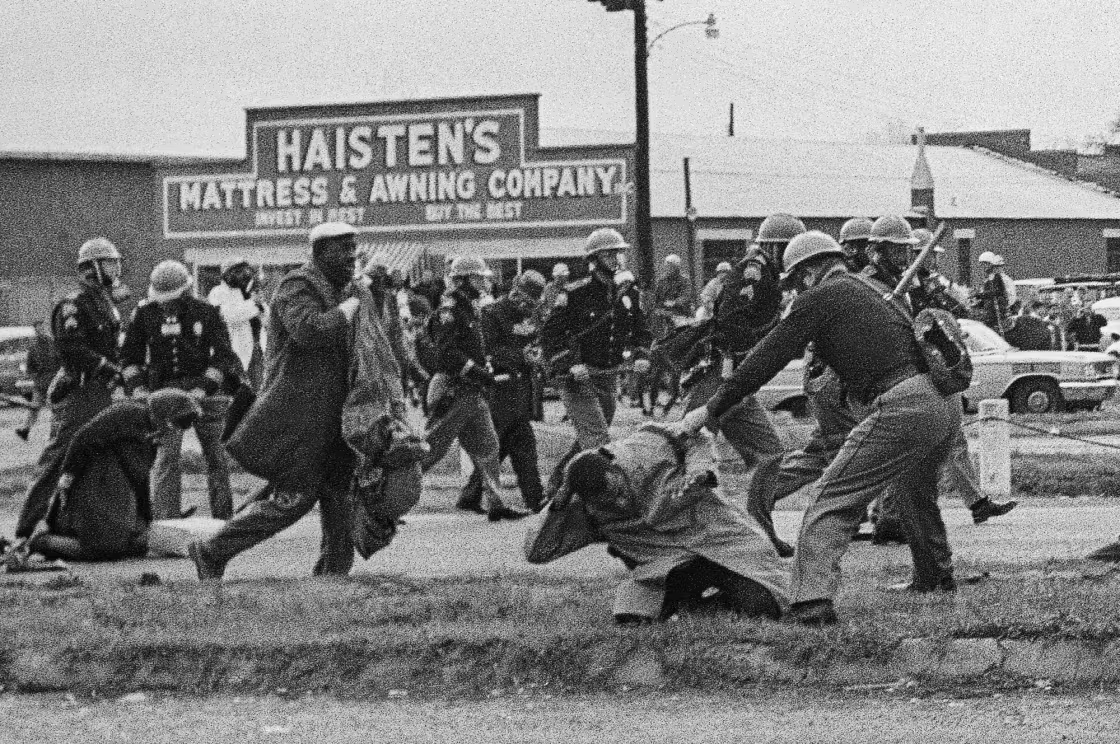

As the marchers reached the middle of the bridge, they were met by a line of state troopers, deputies, and men on horseback. The authorities issued a warning to disperse before they unleashed violence. “Within about a minute, they started using their billy clubs, pushing us back, and then they began beating men, women, and children, spraying tear gas, and using cattle prods,” Mauldin remembers.

On Sunday, March 9, Selma marked the 60th anniversary of what came to be known as Bloody Sunday. The brutal attack that day shocked the nation and helped pave the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The annual commemoration honors those who fought for Black Americans’ right to vote and emphasizes the need to continue the fight for equality.

For many who were there, the anniversary comes with a heavy heart, as new voting restrictions continue to be introduced, and concerns about the direction of federal agencies grow. “This country wasn’t a democracy for Black folks until that happened,” Mauldin said. “And we’re still fighting to make that a more concrete reality for ourselves.”

Speaking from the pulpit of the historic Tabernacle Baptist Church, where the first mass meeting of the voting rights movement took place, House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries acknowledged the historic importance of what happened in Selma. But he also pointed out that the 60th anniversary comes at a time when people are trying to “whitewash our history.” Jeffries told the crowd, which included Rev. Jesse Jackson and several members of Congress, that like the marchers of Bloody Sunday, they too must press on.

“At this moment, faced with trouble on every side, we’ve got to press on,” Jeffries urged.

U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, D-Ala., echoed that sentiment, saying the 60th anniversary comes “at a time when the vote is in peril.” She reminded the crowd of the voting restrictions introduced after the U.S. Supreme Court weakened the Voting Rights Act, particularly the part that required states with a history of racial discrimination to get approval before changing voting laws.

This week, Sewell reintroduced legislation to restore that requirement, named after John Lewis, the late Georgia congressman who led the Bloody Sunday march. The proposal has repeatedly stalled in Congress.

The day’s events culminated in a ceremony and a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Mauldin, who had been in the third pair of marchers alongside Lewis and Hosea Williams, recalls how determined the group was. “It was past being courageous. We were determined, and we were indignant,” he says.

Mauldin took a blow to the head that day and believes the police were trying to incite a riot with their violent response.

Kirk Carrington, just 13 years old on Bloody Sunday, remembers being chased by a white man on horseback, wielding a stick, all the way back to the public housing projects where his family lived. He started marching after witnessing his father being belittled by his white employers when he returned from serving in World War II. Standing in the same church where he had been trained in non-violent protest tactics, Carrington was moved to tears as he thought about the legacy of the movement.

“When we started marching, we didn’t know the impact we would have in America. But now, looking back, we see how it impacted not just Selma, but the entire world,” Carrington said.

Dr. Verdell Lett Dawson, who grew up in Selma, remembers a time when Black people were expected to lower their gaze if they passed a white person on the street. Dawson, Mauldin, and others are deeply concerned about recent efforts to dismantle federal agencies like the Department of Education, as well as attempts to end diversity, equity, and inclusion programs within the federal government.

“Support from the federal government is how Black Americans have been able to get justice and equality,” Dawson said. “Without it, states’ rights will mean the white majority will rule. And that’s the tragedy of 60 years later—we’re seeing a return to the 1950s.”