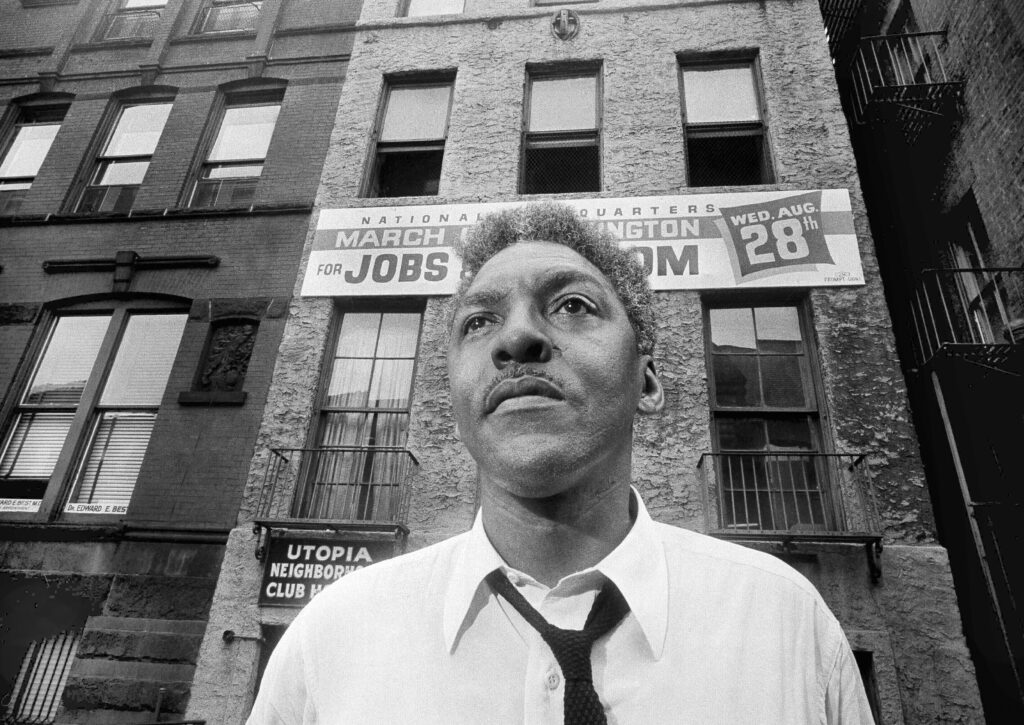

Bayard Rustin, a key advisor to Martin Luther King Jr. and one of the most influential organizers of the civil rights movement, was affectionately known as “Mr. March-on-Washington.” Rustin was deeply involved in organizing and leading protests throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, including the pivotal 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Despite controversy over his homosexuality and past ties to the Communist Party, King recognized Rustin’s unparalleled skills and dedication to the movement. In a 1960 letter, King praised Rustin’s expertise, writing, “We are thoroughly committed to the method of nonviolence in our struggle and we are convinced that Bayard’s expertness and commitment in this area will be of inestimable value.”

Born on March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Rustin was one of 12 children raised by his grandparents. His Quaker upbringing and his grandmother’s involvement in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) significantly shaped his life and commitment to nonviolence. After graduating from West Chester High School, Rustin attended various colleges, including Wilberforce University, Cheyney State Teachers College, and City College of New York.

While at City College in the 1930s, Rustin joined the Young Communist League (YCL), initially drawn to its commitment to racial justice. However, he left the Communist Party in 1941 when its focus shifted away from civil rights. Soon after, Rustin was appointed youth organizer for the planned 1941 March on Washington by trade unionist A. Philip Randolph. During this period he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and co-founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In 1947, he was arrested during CORE’s “Journey of Reconciliation,” a protest testing the Supreme Court’s ban on segregation in interstate travel.

In 1948, Rustin traveled to India to study Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence. A few years later, he visited West Africa, working with independence movements under the auspices of FOR and the American Friends Service Committee. Despite his successes, Rustin’s life was not without controversy. In 1953, after a conviction related to homosexual activity, he was forced to resign from FOR. He later became the executive secretary of the War Resisters League, a role he held until 1965.

Rustin became an important advisor to King during the Montgomery bus boycott. He first visited Montgomery in February 1956 and published his “Montgomery Diary,” in which he expressed a profound sense of the movement’s power. Rustin played a key role in educating King on nonviolence, a principle King had studied but had not yet fully embraced. King valued Rustin’s expertise, organizational abilities, and extensive network, inviting him to be a key advisor despite potential backlash from other civil rights leaders. Rustin’s role with King was multifaceted, from proofreader and ghostwriter to strategist on nonviolence.

Rustin also helped establish the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In December 1956, he proposed the creation of a unified group of Black leaders in the South to amplify grassroots participation in the struggle for justice. At the SCLC’s founding meeting in January 1957, Rustin outlined the group’s goals and contributed to the development of its guiding principles. Although he helped draft much of King’s memoir, Stride Toward Freedom, Rustin chose not to seek credit for his work.

In 1957, Rustin organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom and advised King on the goals of the march and the content of his address. Together with Randolph, he also coordinated the Youth Marches for Integrated Schools in 1958 and 1959.

Rustin’s greatest achievement came in 1963, when he was appointed deputy director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Despite concerns from some civil rights leaders, Rustin’s leadership played a pivotal role in organizing the event, which drew over 200,000 participants to the nation’s capital in August 1963.

From 1965 to 1979, Rustin served as president, and later co-chair, of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an organization focused on racial equality and economic justice through labor activism. From this platform, Rustin championed the idea that progress for African Americans depended on building alliances between Black communities, labor unions, liberals, and religious groups. His work continues to be remembered for its lasting impact on both civil rights and labor movements.